Having been barraged by political verbiage over the past two years, I am reminded of Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s quip that “war is a mere continuation of politics by other means.” Actually, von Clausewitz may have had it reversed, given that several political terms were originally found in the military arena. For example, both “campaign” and “rally” acquired military senses in the 17th century and political ones in the 19th century.

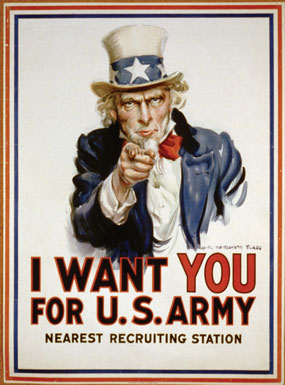

We see an interplay with politics in other domains as well. Take religion — specifically Catholicism, and two common political terms that were born in the Vatican. The word propaganda comes from the Latin phrase sacra congregatio christiano nomini propagando, the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, which was founded in 1622 by a committee of cardinals responsible for foreign missions during the papacy of Gregory XV. It was in the 19th century that the word acquired its political sense: the systematic dissemination of information, often in a biased sense.

And if you find political nepotism as unsavoury as propaganda, again there is a papal connection. It seems the early popes liked to bestow special favours upon their so-called “nephews” (their illegitimate sons) and in Latin the word for nephew is nepos. By the 19th century the word had come to mean an unfair preference for those within one’s sphere of influence.

The language of politics has borrowed from other disciplines. Cynics will not be shocked to discover that a political term has been hijacked from the domain of piracy. I refer to the word filibuster, which derives from the Dutch vrijbuiter and combines the word vrij (“free”) and bueter (“plunderer”). Originally, filibuster referred to 17th-century pirates who pillaged colonies in the Spanish West Indies. However, in the middle of the 19th century, bands of adventurers organized expeditions from the United States, in violation of international law, for the purpose of revolutionizing certain states in Central America and the West Indies. By the end of the 19th century, the word came to refer to long-winded US Senators whose obstructive practices were seen as akin to the havoc created by marauding pirates; they effectively hijacked the agenda of the Senate.

The term caucus in North America refers to the members of a legislative assembly that belong to a particular party. Most etymologists believe that the word was adapted from the Algonquin Caw-cawaassough, which means “counsellor.” The Algonquin word was recorded in a journal by Captain John Smith of Pocahontas fame in the early part of the 17th century with the sense of one who advises or encourages. Caucus first surfaced in New England in the early 18th century and was virtually unknown in British English until the 1870s, when it became a popular political buzzword.

Recently, the electoral district Sarnia-Lambton in Ontario became the champion bellwether riding in Canada, having voted for the winning party in every election since 1963. Both of these italicized words have a political sense that is restricted mostly to Canada. Originally, a bellwether designated the head sheep of a flock whose prize for leadership was having a bell hung around its neck (“wether” is a term for a male sheep or castrated ram). By the 1930s, the sense of “indicating a trend” emerged. The electoral sense of riding, however, is not a Canadian coinage but rather one from Yorkshire, England. Until 1974, Yorkshire was divided into three ridings and the word riding came into English in the 15th century from Old Norse thrithjungr, which originally was rendered riding in English as trithing.

While the word hustings is now used almost exclusively to refer to the rounds of political activity during an election, its origin was quite different. As early as the 11th century, it was rendered singular as husting, which literally means “house thing,” with thing referring to a council meeting. Over time, it referred specifically to the court of law in the Guildhall of London. It was only in the 20th century that it acquired the modern sense of electioneering.

And finally, the current sense of poll as in “going to the polls” arose only in the 17th century. The source of the word is its literal meaning, “head,” and this was its sense starting in the 13th century. One way of counting votes in an election is by counting heads, as seen in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus in 1607 when Coriolanus states, “We are the greater poll, and in true fear they gave us our demands.”

Perhaps the proposed electoral reform in Canada or the election this year in the US will afford some marauding politician the opportunity to hijack other words.

Howard Richler’s book Wordplay: Arranged & Deranged Wit will be published in Spring 2016.