Investors love focus. That was the idea behind the sale of an office real estate portfolio by Fortis Inc., an energy utility. Slate Office REIT, which had renamed itself to focus on offices, was of a similar mind when they decided to buy.

LEXPERT: This deal was about getting that elusive recognition as a “pure play.” By unloading its properties, Fortis could refocus on utilities. And by bulking up on office assets, Slate, which used to be called FAM REIT, could cement its status as a specialty office REIT. So who made the first move?

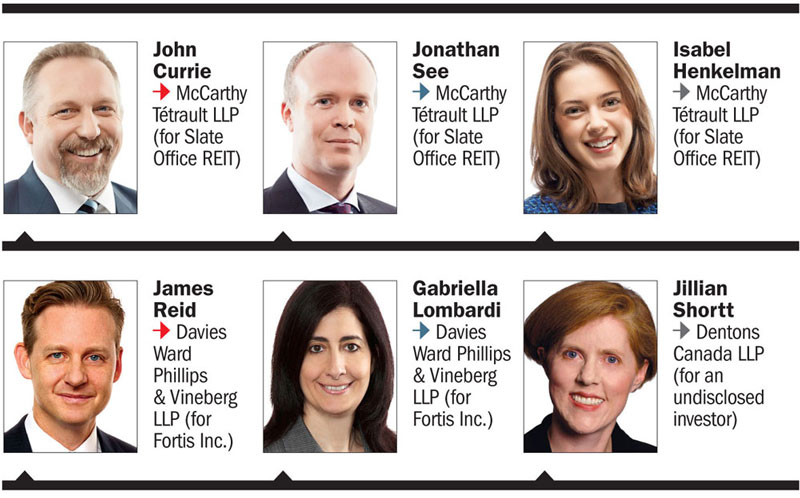

Jim Reid (Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP, for Fortis): It started with Fortis announcing in September 2014 that it was going to conduct a strategic review of the hotel and commercial real estate business owned by its subsidiary, Fortis Properties. All options were on the table, including a sale of shares or assets or an IPO. Incoming CEO Barry Perry was focused on building on the strength of Fortis’s core business in regulated electric and gas utilities. Owning and operating a real estate portfolio no longer fit with the business strategy.

Gabriella Lombardi (Davies): We looked at selling the entire portfolio in a single deal, but hotels and office buildings are distinct asset classes that attract different buyers.

LEXPERT: And that’s where Slate comes into the picture, right?

John Currie (McCarthy Tétrault LLP, for Slate Office REIT): The transaction was a great representation of Slate’s strategic repositioning and focus on office assets. The portfolio comprises some of Atlantic Canada’s highest-quality commercial buildings, which are flagship properties in their respective markets. It nearly doubled the REIT’s asset base.

Lombardi: Once Slate signaled its interest to expand its office footprint, this deal came together very quickly. A letter of intent was signed and the legal deal teams got to work negotiating the purchase agreement.

LEXPERT: Were there any other key drivers behind this deal, besides just a refocusing of the respective businesses?

Reid: For Fortis, this was a strategic decision to sell non-core assets that amounted to 3 per cent of its total assets. So, yes, this reflected Fortis’s strategy to focus its capital expenditure plan on growing its core business and diversifying its asset base in the regulated utility and energy infrastructure space. The objective of the deal was to maximize value and sell on an expedited basis.

Jonathan See (McCarthy): Another key driver involved the strategic partnerships made by Slate. There was a public offering of subscription receipts of the REIT with a syndicate of underwriters, co-led by TD Securities and BMO Capital Markets; two bank facilities; a $35-million private placement of REIT units to Fortis Inc.; and co-ownership of three of the properties with a Canadian institutional real estate fund.

LEXPERT: Dentons represented this institutional investor, correct?

Jillian Shortt (Dentons Canada LLP, for an undisclosed investor): Our team was heavily involved on behalf of our client, who entered into a co-ownership agreement with Slate for a number of the properties, from about a month before closing.

LEXPERT: Lots of players in this one. Is it fair to say that all sides were highly motivated, and if so, did that speed up the process?

Lombardi: Both sides were highly motivated — Fortis wanted to exit the commercial real estate business, and Slate wanted to expand its holdings in Canada.

Shortt: The vendor, the purchasers and the lenders were all motivated to get the deal across the finish line. That not only sped up the process but helped the parties get all of the sale documentation and the co-owner and financing documentation settled fairly smoothly and very quickly.

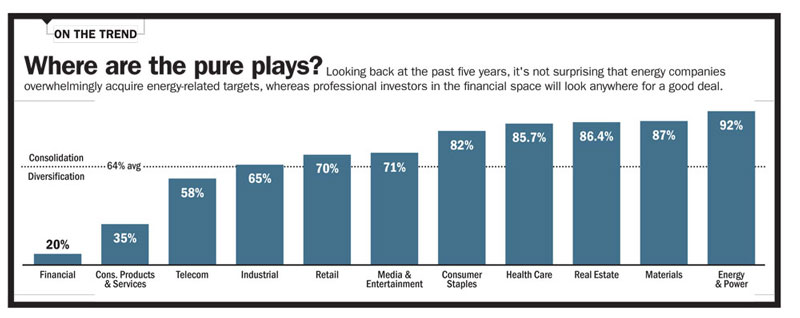

LEXPERT: Generally speaking, are companies refocusing and moving toward pure plays more often these days as the economy slumps and public companies look to inspire investor confidence?

Reid: Owning non-core assets is rarely rewarded by the market and can give activists an opening to argue that management lacks focus. For Fortis, this was a deal that just made good strategic sense and the timing was right – they were taking a pause after completing major acquisitions in 2013 and 2014. This was a high-quality real estate portfolio, but there was no compelling rationale for Fortis to continue to own it.

See: For Slate, this was about using the knowledge and expertise of its team and focusing on undervalued assets.

LEXPERT: There was lots of legal representation on this deal. And yet the deal closed in short order — just one month after announcement on May 21. Did having so many parties offer any twists?

Lombardi: The portfolio included 19 properties, so there were lots of issues to work through. In some cases an office building was connected to a hotel, and it was challenging to negotiate arrangements acceptable to Fortis, Slate and the hotel buyer. But the negotiations were business-minded and pragmatic, and we were able to avoid getting bogged down fighting over side issues. A comprehensive data site was available to Slate for a number of weeks prior to the announcement of the deal, and the parties were highly incentivized to find solutions that would work for both parties.

Isabel Henkelman (McCarthy): We were all fortunate enough to be dealing with very goal-oriented sophisticated parties.

Shortt: And it helped that each of the lead lawyers had worked with each other on prior deals. There was a level of understanding and co-operation between the parties that isn’t always there on deals of this size and complexity. That, and a number of late night calls with all clients and lawyers, made the difference.

LEXPERT: Were there any risks that might have prevented this deal from closing?

Reid: Slate needed to have its joint venture partner and lenders on board and execute a capital-markets financing. Fortis agreed to support this by investing $35 million in Slate’s publicly traded REIT units. As a motivated seller, Fortis was prepared to be flexible and creative to get the deal done.

See: Both parties were interested in conducting and expediting the closing of the deal. This short closing period meant the window to addressing any issues was small. We were faced with the traditional regulatory issues associated with such a transaction, but were able to handle all matters in a timely manner.

LEXPERT: Given that Fortis was selling its real estate portfolio, did this necessitate a winding down of Fortis Properties?

Reid: Fortis Properties was in the process of selling substantially all of its assets, so Fortis, as the parent company, agreed to stand behind the obligations of Fortis Properties under the purchase agreement. There was no need to wind down Fortis Properties as part of the deal, although Fortis may decide to do so in the future.

LEXPERT: Was it a memorable deal? What are you going to take away from this one?

Lombardi: From our perspective, one of the most interesting aspects involved the Delta Brunswick/Brunswick Square property. This was a highly integrated office building and hotel complex. Severing the properties would have been very challenging, and it was unclear whether Slate or the hotel purchaser would take it. In the end, we were able to negotiate a deal with Slate that worked for everyone.

Shortt: It was complex and fast-paced. While there were lots of different disciplines involved on the legal side, it was a real estate deal at its core.

Currie: Notwithstanding the complexity, multiple stakeholders and aggressive timelines, everyone worked collaboratively. The deal was transformational in that it cemented Slate’s status as an office REIT with a truly national footprint.

(For a summary and full list of legal advisors, click here)