The story of the business side of the mining industry this past year is one of competing forces resulting in contradictory and often unexpected outcomes. Still, lawyers say, overall, it has been a great time to be involved in mining.

“I like to say to people, especially around our firm and my friends outside of the mining industry, that for once, the industry is not entirely wearing a black hat because of the role it’s playing in the energy transition,” says Michael Pickersgill, a partner at Torys LLP and head of its mining and metals practice. “Suddenly, being part of the mining sector is actually being part of the solution instead of just being someone who pollutes, and that creates a bit of a tailwind, psychologically, for a lot of the participants in the industry, which is great.”

The opposite of tailwinds, however, is headwinds. While the global push to switch from carbon-intensive fossil fuels and into renewable power and battery-electric systems, especially in vehicles, has created awareness and demand for critical minerals and battery metals, there are also the broader macro-economic trends of inflation, rising prices, and supply chain tightness, says Joanna Cameron, partner at Osler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP.

“There are the headwinds of increased inputs. While you’ve got revenue, you don’t have as much margin, so the exploration spend has gone down, and that has put some companies, the mid-tier developers, into an M&A play because projects are just more expensive than anybody thought.”

Mining M&A by the numbers

Globally, mining-sector dealmakers have been busy in 2023, mainly focused on energy-transition metals and critical minerals. “So far, in 2023, there has been about $22 billion worth of proper M&A” launched, says Ivan Grbesic, partner and co-head of the mining group and head of the Latin America coverage group at Stikeman Elliott LLP.

The interest in critical minerals and energy-transition metals has carried over from last year. And Grbesic expects the same will happen next year. Breaking down the 2022 M&A figures, he notes copper deals amounted to 56.1 percent of M&A activity, gold deals 35 percent, and critical minerals accounted for the remainder.

“And it’s interesting to note from a geographic perspective that Canada and Australia were the favourite target countries over the last year or so: between the two of them, they hosted about 45 percent of the companies and projects targeted in 2022, with about 69 percent of the total deal value being in those two countries.”

Speaking of Canada and the Canadian market, 2023 has been good and bad, according to Pickersgill. His numbers show that M&A activity is down and the transactions are smaller. Year to date, only $9 billion in transactions have occurred. By the end of both 2022, $19 billion worth had been signed. The figures, however, don’t tell the whole story.

“I would say it’s been a big year. M&A activity and traditional corporate finance have been down in 2023, but you wouldn’t know it by the number of things going on in the industry. I think the health of the industry itself in Canada … can’t really be correlated to how many M&A deals have been completed in 2023,” says Pickersgill.

Beyond M&A inside and outside of Quebec

Quebec also had a big year and benefits from what René Branchaud, a partner at Lavery, calls a lithium rush. This mainly occurred in the James Bay region.

“We negotiated and signed a lot of deal option agreements and joint venture agreements between major companies such as BHP and Rio Tinto and junior exploration companies, and also with Australian mining companies coming here to acquire mining rights. We saw an increase in M&A, but not much financing, except for major companies like BHP and Barrick signing agreements to invest tens of millions of dollars in exploration in Quebec, so that was new in 2023.”

As with other parts of the country, mining companies and projects in Quebec that aren’t being swept up in the M&A process are receiving interest from the business community.

“We will see, during the fall or before the end of the year, there will be a lot of flowthrough financing done to finance the junior companies to pursue their exploration programs,” says Branchaud.

Royalty deals are also gaining in popularity among investors, and in La Belle Province, that is leading to a new practice that has cropped up over the past couple of years – signing a “hypothec.” Branchaud describes this arrangement as “the equivalent of a mortgage” that is recorded at the province’s land registry and that protects the creditor’s right to be paid in the future.

Mining’s geopolitical factors

Last October, the Canadian government ordered three Chinese-based companies to divest their interest in Canadian lithium companies. It also released a policy to keep the control of critical minerals in the hands of Canadians or, at the very least, in the hands of like-minded allies.

But Canada isn’t the only country to re-evaluate its stance on foreign ownership. It is happening around the world. Some countries are offering incentives to domestic miners. The US used the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to support mining. Canada is offering $3.8 billion as part of its critical- minerals strategy. Some countries are tightening control over foreign activity in the sector by changing royalty rates or tax regimes. Others are going further, such as Chile, which nationalized its lithium industry in April. All of this means more risk for companies engaged in international M&A activity.

“It depends on the jurisdiction, definitely, but you’re going to have to price in the risk. I’ve got some junior clients who are even engaging lobbyists in some areas of the world to try to influence government policy, which I haven’t seen before,” says Cameron.

Other metals and minerals

Mining has always been diversified, and this past year has been no different. Gold, for example, has garnered the attention of opportunistic dealmakers.

“We’re seeing the gold consolidation trend continuing due to a desire for portfolio optimization, building scale and synergies,” says Grbesic. “At the beginning of this year, news broke about Newmont’s proposed acquisition of Newcrest, which was almost US$17 billion. And we heard that that deal was recently approved by Australian regulators, making it potentially the third-largest M&A deal in Australian history. We saw a whole bunch of consolidation happening leading up to that deal.” Newcrest’s Red Chris and Brucejack are both in BC. Newmont’s Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine and Porcupine Mine are in Ontario.

Grbesic calls out one deal in the gold sector, which was completed this year – Pan American Silver and Agnico Eagle acquiring Yamana Gold – as representative of another trend that has cropped up recently: syndicated acquisitions where two or more parties take interest in different parts of the target company. “We expect that we will be seeing more of that in the years to come.”

Unlike the relatively steady interest in gold, the demand for uranium has waxed and waned, but interest in the radioactive metal has been heating up, says Cameron.

“People are expecting it’s going to hit its metrics. And the algorithms are predicting it’s going to hit a bull run that’s been over 10 years in the making. Some of that is banked on geopolitical uncertainties. Some is because governments are adapting their stances on clean energy and building reactors.”

Canada announced a $29.6 million small modular reactor program in February, says Cameron, and countries such as Sweden may reverse their moratoriums on mining for uranium.

Divesting dirty investments

While energy-transition metals have been in the spotlight this year, a dirtier asset has also received a lot of attention: coal. Switzerland-based Glencore is attempting to buy Teck Resources’ metallurgical coal business – the kind of coal used in steelmaking – to combine with its thermal coal business, which is coal burned to generate electricity. Glencore then plans to spin it all out into a separate entity. And while no deal has been reached between Vancouver-based Teck and Glencore, let alone approved by regulators, the proposal has given the industry lots to consider.

“Coal is a big, hot topic because it’s not ESG [environmental, social, and governance] friendly, but we’re still using it. We’re not fully transitioned. We know it’s not great for the environment, but it’s really good business right now,” says Cameron. She adds there are still buyers willing to invest in the carbon-intensive sides of the mining industry, even if a growing number of shareholders are pushing companies to be cleaner and greener.

New mining players

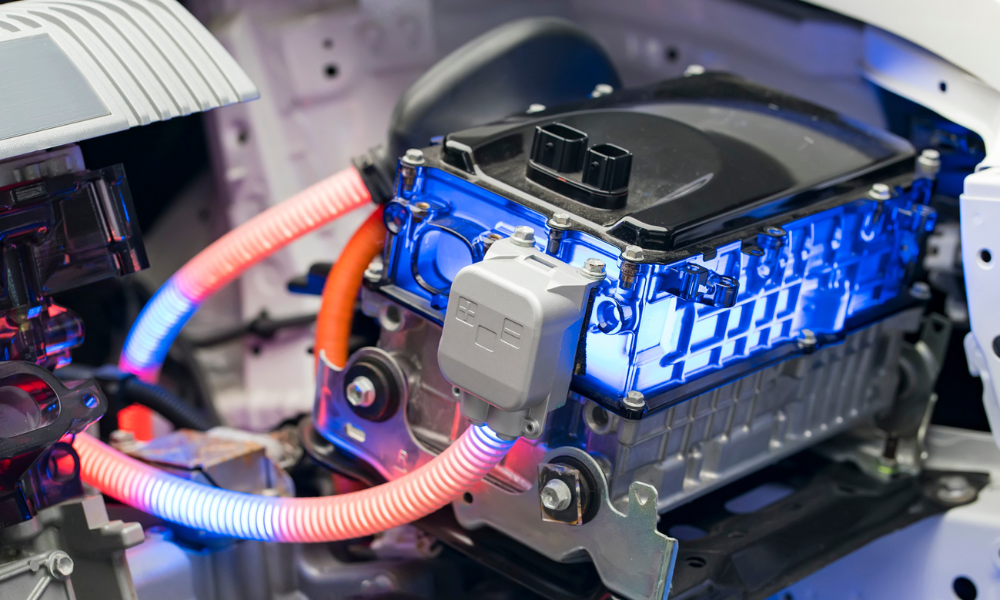

Countries worldwide believe that one way to be cleaner and greener is to end the sale of vehicles with internal combustion engines. So, companies throughout the battery-electric supply chain have begun making mining or mining-related deals – often with financial backing or government partnerships. In Quebec, for example, Branchaud says construction is underway on plants that will transform lithium into batteries or recycle existing batteries.

Naming some of the most significant deals of this kind, Pickersgill says, “If you want to think of the splashiest of names, we’ve seen GM put significant capital into Lithium Americas this year; Ford Motor Company entered into a series of off-takes with a variety of different lithium producers, including some in Quebec; Volkswagen has made a significant investment, similarly into mining assets, but critically into the development of downstream processing of battery metals. And that trend will continue.”