In the modern legal market, lawyers must spare no effort to find solutions to their client’s needs. Litigators face escalating demand to communicate their advice in clear, impactful, and efficient ways. Clients are also under unremitting pressure to quantify litigation risks to their internal stakeholders, particularly in monetary terms.

Decision tree analysis can satisfy these objectives. Although the idea of applying decision trees to civil litigation has been around for decades, most litigators have not integrated them into their practice. The reasons for this vary, including lawyers reluctant to think and communicate in term of numerical probabilities.

It is time for that to change. Using decision trees to model litigation gives lawyers an opportunity to communicate their case assessments in a compelling, client-centric way. Decision trees allow lawyers to explain a dispute visually, with easily digestible language and numbers. A single page can convey as much information as a lengthy written opinion. Advances in technology has made it easier for lawyers to develop decision trees and share them with clients. As such, this technique ought to become a standard offering for litigation clients.

What is a case assessment? What do clients need from them, how do lawyers meet such needs, and how do lawyers sometimes fall short?

A case assessment is simply a lawyer’s analysis of a party’s litigation risk and strategic options. This analysis usually also involves evaluating the probability of success or failure of each of these options, along with the consequences.

In a good case assessment, a lawyer will gather information relating to the case – facts, law, the client’s risk profile and objectives, etc. – and apply their professional judgment to predict the likelihood of different litigation outcomes and recommend a course of action. In an excellent case assessment, a lawyer will communicate this analysis in a way the client genuinely understands, placing them in the best possible position to make informed decisions.

Case assessments are commonly conducted at the outset of a matter and in advance of, or following, major steps in litigation (discovery, mediation, trial, etc.). That said, a case assessment can be conducted at any point provided there is sufficient (new) information.

Litigants need clear, actionable advice, whatever the complexity of the case. They also need to understand the “big picture” and where the significant inflection points in the case lie. But clients are busy, so information must be conveyed efficiently. In addition, clients frequently wish to communicate to their internal stakeholders in terms of numbers and dollars.

Notwithstanding best efforts, lawyers sometimes lose track of these needs. When describing probability, litigators often use vague terms such as “possible”, “good chance,” “highly likely,” and so forth. They can also be reactive, too focused on the immediate issues and the steps required, rather than on the overall trajectory of the case, the critical case junctures (from both a risk and cost perspective), the range of realistic outcomes, and the financial consequences. Litigators may also be tempted to focus too much on legal minutia, or on the issues that seem most interesting to them, rather than impactful to their clients. Email reports to clients on their cases often run up into thousands of words and legal opinions into dozens of pages.

The net result may be a potential disconnect: the litigator may not be providing optimal advice for the litigant’s decision-making needs. This is where decision trees come in.

What is a decision tree as applied to litigation? How can they help lawyers communicate case assessments to clients?

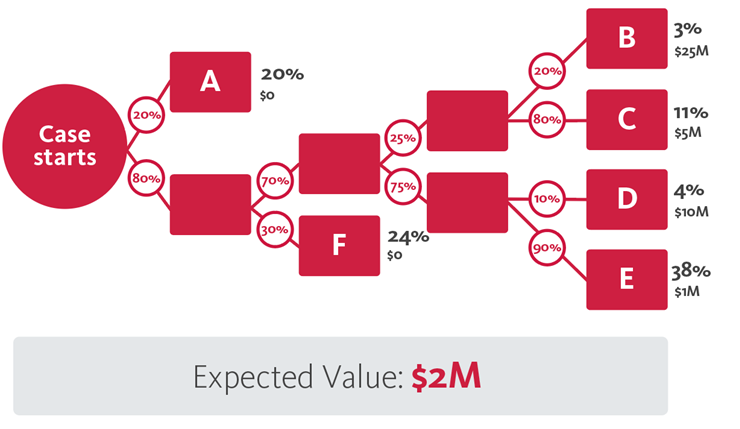

A decision tree is a way of modelling litigation. It maps a case onto an easy-to-follow diagram of decision points, risk, and monetary outcomes.

To prepare a decision tree analysis of a case, a lawyer must leverage their knowledge of the matter and their professional judgment. The basic steps involve:

- Depicting the ways a case could develop, from start to finish, with the case initiating from a “root” and then “branching” into a range of junctures and outcomes;

- Estimating the financial result of each ultimate outcome, factoring for damages awards, adverse cost awards, and the client’s litigation costs, as applicable; and

- Assigning a percentage probability to each point throughout the decision tree, which is then used to calculate the probability of each ultimate outcome.

With these steps complete, the lawyer can develop risk-weighted settlement recommendations. This starts with calculating the “expected value” of the case, which is a probability-weighted average value of the case’s potential financial outcomes. Or to put it more simply: if this case were to be tried 100 times in court, what would be the average of the court’s awards given the probability of each ultimate outcome and its financial consequence? In essence, the expected value is the financial result for the client, were it possible to “play the averages” of the case.

Typically, expected value is only a starting point for identifying a reasonable settlement value. The lawyer must still consider other factors, such as the opposing party or parties, opposing counsel, the client’s objectives and risk profile, and any internal data the litigation department may possess from comparable cases. Nevertheless, expected value is always a useful benchmark.

We must also note that a decision tree analysis of a case will, as with any case assessment, involve assumptions. These must be clearly flagged.

In our experience, clients are very receptive to case assessments based on a decision tree analysis. This kind of overview makes it easier for them to identify true inflection points in a matter. The decision tree also communicates, in clear terms, the lawyer’s estimate of the probability of each potential outcome and the rationale for settlement recommendations. It is also an efficient way to convey a lot of information. Finally, clients themselves often use decision tree analyses in their own businesses, and thus welcome this approach when working with their lawyers.

What technology is available to assist lawyers with doing decision tree case assessments? What limitations should lawyers be aware of in using this technology?

Manually constructing a decision tree and making the related calculations can be tedious and time-consuming, particularly with complex litigation, and with lawyers who are less comfortable with mathematical probability.

This presents an opportunity for technology. While decision trees can undoubtedly be built through Excel, or other spreadsheet technology, until recently there was a lack of litigation-specific technology to support this process. And what software was available was not user-friendly. It was usually not designed with litigation specifically in mind (only as one of multiple use cases). The user experience was also awkward and clunky. Some of these tools were expensive and the trees they produced were not typically aesthetically engaging. We believe this gap has likely been an important factor in the low level of litigators adopting this technique (though not the only one).

Fortunately, there are now better options. They are designed for use in litigation, by litigators, or with input from them. They not only provide functionality for developing basic decision trees, but also offer more sophisticated features (e.g., sensitivity analysis, comparing multiple scenarios, etc.). The latest decision tree tools are also cloud-based. From a technical perspective, this makes deploying them straightforward once data security is addressed.

At Osler, we use a decision analysis tool called Litigaze. It is powerful, user-friendly, and visually appealing.

As helpful as this new technology can be, it does not, and cannot, replace or even reduce the litigator’s role in performing a case assessment. These tools only help the lawyer build the decision tree, automate the calculations, and present the tree. The litigator must still gather all the relevant information and use their professional judgment when inputting data into the tool, interpreting the results, and forming their advice and recommendations.

Once a firm or inhouse legal department has decided to use decision tree technology, how can they integrate it into their decision-making process? Do these tools require added training for lawyers or IT staff or an external firm to operate?

The key to integrating decision tree analysis into the operations of a litigation department is training and awareness.

First and foremost, lawyers must understand how a decision tree works, the types of information it can provide, and how this information can be leveraged to enhance their legal advice. This is sometimes the greatest barrier because some lawyers are uncomfortable with new techniques or are satisfied with their present practices.

However, once this understanding is in place, using modern decision tree software typically requires minimal additional training. Law firm lawyers should also be reminded, prior to modelling any client’s matter, to check the client’s outside counsel guidelines to confirm using the software is permissible. In some instances, client consent may be required.

The demand on an IT department should also be minimal, beyond any initial and recurring security reviews. As cloud-based services, the burden to maintain and provide technical support for the software is largely on the vendor.

The next step to success is raising and maintaining awareness of the decision-tree technique. Lawyers rely on established workflows to maintain optimal efficiency. It can be easy to overlook new strategies to addressing a client’s requirements. The litigation department must find ways to remind the legal professionals this technique is available, such as offering training, consultations, resources on the department intranet, and other forms of support. In addition, an emphasis on the client value and the benefits this process may have to a litigator’s practice can help encourage adoption. Many litigators have told us that going through the process of creating and thinking about a decision tree has given them a greater appreciation and understanding of their case.

Clients should also be made aware the litigation department can apply decision trees to case assessments of their matters. Nothing motivates a lawyer to try something new like a request from a client!

The legal sector has a reputation of being notoriously slow to adapt to technological innovation and changes to established methods and structures. How would you seek to convince a more traditional lawyer of the merits of this new technology?

Although technology has a critical role to play in applying decision trees to case assessments, the underlying methodology is not new. Decision trees are a component of an established field of academic study. They are used in a range of industries, including healthcare, insurance, and finance. Whereas specialized expertise used to be preferable to draw and perform the calculations that constitute a decision tree, this is no longer the case. The decision tree tools we are describing do not replace the lawyer’s role in doing a case assessment. Rather, they enhance it. They simply make it easier for the lawyer to develop a decision tree, which makes applying this approach to a case assessment a realistic and compelling option.

How can firms and inhouse legal department measure the impact and the overall success of decision trees in litigation?

Client satisfaction is the best benchmark. Lawyers and clients alike should not assume that applying a decision tree analysis to a case assessment will inevitably require less time than a conventional approach. This is still a lawyer-centered, not machine-centered, technique. The only portions of the analysis the software automates are the calculations relating to probability and expected value, and the drawing of the tree. Lawyers must still do all the heavy-lifting relating to research and analysis.

The primary attractions to using a decision tree in a case assessment is that, in the right circumstances, it ensures that litigator and client are on the same page as to possible outcomes and probabilities of a case. It also puts the client in an optimal position to not only make informed decisions about their case, but to clearly communicate the reasoning behind those decisions to their internal stakeholders as well.

***

Gillian Scott is Litigation Operations & Products, Partner at Osler. In her unique, dual business-side role, Gillian supports the National Litigation Department’s strategic operational goals and provides leadership to the firm on the management of Osler’s innovative legal product offerings. Gillian is focused on transforming the business of law through practical and incremental change based in talent, process improvement, informed data analysis and technology.

Gillian Scott is Litigation Operations & Products, Partner at Osler. In her unique, dual business-side role, Gillian supports the National Litigation Department’s strategic operational goals and provides leadership to the firm on the management of Osler’s innovative legal product offerings. Gillian is focused on transforming the business of law through practical and incremental change based in talent, process improvement, informed data analysis and technology.

Charles Dobson is the Knowledge Management Lawyer for Osler’s Litigation and Dispute Resolution team. He works closely with the Firm’s litigators to deliver excellence in client service. Charles ensures the Firm’s institutional knowledge is captured, refined, and accessible.

Charles Dobson is the Knowledge Management Lawyer for Osler’s Litigation and Dispute Resolution team. He works closely with the Firm’s litigators to deliver excellence in client service. Charles ensures the Firm’s institutional knowledge is captured, refined, and accessible.

Jennifer Thompson is the Head of Osler Works – Disputes, which houses Osler’s Discovery Management Services, along with other litigation solutions. Jennifer’s previous commercial litigation, project management and knowledge management experience make her uniquely positioned to facilitate Osler’s delivery of cutting-edge legal services.

Jennifer Thompson is the Head of Osler Works – Disputes, which houses Osler’s Discovery Management Services, along with other litigation solutions. Jennifer’s previous commercial litigation, project management and knowledge management experience make her uniquely positioned to facilitate Osler’s delivery of cutting-edge legal services.

Mark Sheeley is an Associate in the Litigation group at Osler. He has a wide-ranging corporate-commercial litigation practice, with expertise in complex class action litigation and matters relating to securities, tax, insolvency, administrative law and internal investigations.

Mark Sheeley is an Associate in the Litigation group at Osler. He has a wide-ranging corporate-commercial litigation practice, with expertise in complex class action litigation and matters relating to securities, tax, insolvency, administrative law and internal investigations.