Jean Monty, the no-nonsense, bottom-line driven Chairman of BCE Inc., has given himself two years to pull it off. As reported in the National Post in early April of this year, Monty acknowledged that \"BCE will consider options including breaking itself up if its bet on the convergence of the telecom and media industries does not pay off in the next two years.\"

This is an alarming admission given that it was only in mid-September of last year that BCE, The Thomson Corporation and The Woodbridge Company Limited created the new telecom/media giant Bell Globemedia that brought together a number of Canada\'s leading media brands, including CTV and The Globe and Mail. Bell Globemedia was but one in a series of convergence deals that swept through the Canadian market, including BCE\'s acquisition of CTV, CanWest Global\'s acquisition of more than 200 publications from Hollinger, Quebecor\'s acquisition of Groupe Vidéotron, and Rogers Communications\' decision to buy into the Toronto Blue Jays baseball team.

But, for BCE, the early hopes for the development of new, converged services have not been met. While remaining convinced as to the long-term benefits of convergence, Monty conceded that BCE\'s shares were currently trading at a 35 per cent discount to the stand-alone value of its individual businesses. The BCE Chairman also said that unless it was able to successfully \"package\" new digital services, BCE would eventually be relegated to the role of a low-margin provider of wholesale network capacity.

Corporate Canada has bet heavily on the convergence business model. So has Gowlings.

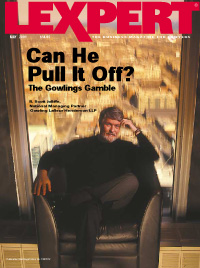

Scott Jolliffe is the National Managing Partner of 500-lawyer plus Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP, a national full-service law firm widely recognized as having one of Canada\'s top intellectual property (IP) practices. IP and IP advocacy, without question, are the firm\'s crown jewels. Gowlings has big ambitions. Jolliffe, like Jean Monty, operates on short time lines. Jolliffe has given himself under five years to pull it off. The \"it\" in question is turning Gowlings into a top-tier corporate/commercial law firm.

Like BCE, Gowlings has engaged in a recent series of audacious mergers: Code Hunter in Calgary, Lafleur Brown in Montreal, Montpellier McKeen Varabioff Talbot and Giuffre in Vancouver, Ballem MacInnes LLP again in Calgary, and may shortly announce what is arguably the most important merger to date, Smith Lyons LLP in Toronto. In short order the principally Ottawa- and Toronto-based firm has transformed itself into a major national, full-service platform.

And, again like BCE, the business model that is driving Gowlings is convergence; in this case the convergence of IP, information technology (IT), and corporate/commercial transactions. The concept has been successfully implemented by top-ranked IP and IT practices in both the UK and US, i.e. Bird & Bird in London and Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati in Palo Alto. The strategy is to target emerging and mid-sized New Economy companies and provide them with the entire panoply of legal services, i.e. corporate, financing, joint venture and distribution agreement work, etc., that converge with and are driven by the needs of their IP and IT products. Simply put, Gowlings intends to lever off its top-tier IP practice to enter the big leagues of corporate work.

But Gowlings wants more. It wants to enter the top-tier of corporate work where the big sharks, like Oslers, McCarthys and Blakes, feed. And it wants to do so in relatively short order, under five years. And again, like BCE, particularly in terms of short-term results, skeptics abound. So: who is Gowlings; who is Jolliffe; and can they pull it off?

At the beginning of the 1980s, Gowling & Henderson (the predecessor firm) was in an enviable position. Gowlings dominated the Ottawa market. With 80-plus lawyers it was the seventh-largest law firm in Canada. Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP was the largest with 120-plus lawyers, followed by McCarthy & McCarthy (subsequently McCarthy Tétrault) at 110 plus, and Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP at 100 plus. The firm enjoyed then, as it does now, an international reputation for its IP practice. But it also had an important advocacy practice spanning a broad range of counsel work, with an emphasis on the Supreme Court of Canada, the Federal Court and federal regulatory work, including the then esoteric areas of competition, customs and Foreign Investment Review Agency mandates.

But Gordon Henderson, Q.C., the power behind Gowlings, was not content with the firm remaining a big fish in a small pond. In 1980, Scott Jolliffe was a junior associate with Gowlings when he was invited, with three other colleagues, to relocate to Toronto to open a new office. The timing struck many as odd. The economy was in the grip of a recession and Toronto is one of the most, if not the most, competitive legal market in the country. As Jolliffe recalls, \"none of the Toronto firms felt threatened by us.\" In fact, he adds, \"many of the Bay Street firms didn\'t even notice our arrival.\"

The Toronto office was quick to grow in the firm\'s traditional areas of strength. In IP, Jolliffe built the practice from the ground up and its advocacy practice pole vaulted into prominence with the firm\'s merger with Toronto-based Cameron, Brewin & Scott in 1983. \"But our business law practice grew much more slowly,\" Jolliffe acknowledges, \"because Toronto was and remains well-serviced by excellent law firms.\"

The situation changed in 1989, when Gowlings merged with 60-lawyer Strathy, Archibald & Seagram, a respected mid-sized Toronto business law firm with strengths in banking (with CIBC as the primary client), insolvency, corporate and transportation law. \"That was a terrific move, because Strathys\' depth in bankruptcy and restructuring carried us through the recession of the early 1990s,\" Jolliffe recalls, \"and our business law practice strengthened in that period.\"

However, the earlier 1986 merger with 23-lawyer Simmers, Harper, Jenkins, based in Kitchener and Cambridge, Ontario, had faltered. \"The rationale for that merger was confidence in the future of the technology-driven industry in that region, where our IP practice was a natural fit,\" Jolliffe says. But the recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s hit the economy in the region earlier and deeper. \"The work wasn\'t there and that delayed the implementation of our strategy,\" Jolliffe recalls. \"But we stuck with it.\"

Sticking with it paid off. In 1995 the area, now known as the Waterloo region, took off as an incubator for high-tech start-ups and Gowlings\' business technology practice grew commensurately. When high-tech became the foundation of the New Economy, Gowlings was well positioned to take advantage of the development.

The belated success of the business plan behind the Simmers, Harper merger was, in fact, the precursor for a more ambitious game plan. \"In the mid 1990s, we re-evaluated ourselves and our future,\" Jolliffe says, \"and developed a strategy that envisioned a national platform which would enable us to establish tier-one practices in IP, advocacy and business law, our three main professional services areas.\"

Important planks in that national platform fell into place with the 1999 merger with Calgary\'s Code Hunter and the 2000 merger with Montreal\'s Lafleur Brown. Code Hunter was generally seen in the Calgary market as a second-tier corporate firm (Gregory Turnbull is an important player) with a very strong advocacy practice, i.e. Alan D. Hunter, Q.C. Lafleur Brown was generally seen in the Montreal market as a second-tier corporate firm with a number of key players such as Luc Lissoir in corporate finance and Charles Bradeen, Q.C., in asset-based financing.

Thus, by the close of 2000, at 500-plus lawyers, Gowlings had built the fourth- or fifth-largest law firm in Canada (depending on the head count on any particular day), trailing only McCarthys (at 677), Borden Ladner Gervais (at 573), Fasken Martineau DuMoulin (at 518), and Fraser Milner Casgrain (at 507). A remarkable accomplishment.

Yet the top corporate law firms that grace Bay Street\'s corridors of power were notably unimpressed. In their view the mergers had done little to move Gowlings closer to its stated goal of becoming a tier-one business practice. As one senior corporate lawyer, who spoke off the record, noted: \"They\'re still not on the radar screen. It would be a serious mistake to confuse Gowlings with what McCarthys put in place in 1990. McCarthys started from the position of being a top corporate practice in Toronto with a blue-chip client base and merged with Clarkson, Tétrault in Montreal and Shrum, Liddle & Hebenton in Vancouver, which were important corporate practices in their own right. That\'s very different from what has happened here.\" Jolliffe, with characteristic candour, does not overstate his case. \"Access to the upper tier of corporate finance requires more than the current practice that Gowlings enjoys,\" he acknowledges.

So what will it take to vault Gowlings into the big leagues of corporate work?

In March of this year, Gowlings and Ballem MacInnes LLP announced a merger of their respective firms effective May 1. Ballems is a respected 26-lawyer oil and gas and generally corporate practice. The Oil and Gas Lease in Canada by senior partner John Ballem, Q.C., is considered the definitive text in this practice area. With the addition of the Ballem MacInnes lawyers to the former Code Hunter, Gowlings will have become, within the space of two years, the third- or fourth-largest law firm in Calgary, trailing only Bennett Jones, Macleod Dixon, and possibly Fraser Milner Casgrain.

Perhaps more important, however, is what is afoot in Toronto. The on-again, off-again Gowlings/Smith Lyons merger negotiations are on again. But what is significant this go around is the removal of an important impediment. Smith Lyons has a major energy practice, acting as corporate and regulatory counsel to a number of very large utilities, across Canada and elsewhere. Gowlings has a strong labour relations practice on the union side (acquired with the 1983 merger with Cameron, Brewin & Scott) involving workers in the energy sector. The conflict is obvious.

Gowlings and two of its senior litigators, Chris Paliare and Ian Roland, are close to an agreement whereby Messrs. Paliare and Roland and up to sixteen of their colleagues will leave the firm to set up a separate commercial litigation/labour relations boutique practice. The significance of this development reaches beyond the immediate conflict with Smith Lyons.

The 1983 merger with Cameron, Brewin & Scott had been a good fit at the time in that the Camerons advocacy practice (led by the distinguished Ian Scott, Q.C.,) complemented the respected counsel practice that Gowlings, led by Gordon Henderson, had built in Ottawa. But the strategic direction of the firm had changed. It had become increasingly difficult to maintain a diverse and often plaintiffs\' litigation practice and a union-based labour relations practice within a firm that now saw itself as a corporate practice. The departure of top-ranked Paliare and Roland demonstrates some of the costs Gowlings is prepared to accept in pursuit of its goals.

\"The Smith Lyons talks simply crystallized what was inevitable,\" says Paliare. \"It is simply too hard to maintain a broadly-based litigation practice in the context of what Gowlings is today and where the firm is going. If it weren\'t Smith Lyons, it would be someone else. I think Scott Jolliffe\'s moves to make Gowlings a top corporate firm make strategic sense. Our departure is an endorsement of Gowlings, its direction and its leadership.\"

With respect to the Gowlings/Smith Lyons merger, while it may be too early to start picking out curtains, there is guarded optimism. Senior members of both firms are hopeful that \"a [merger] announcement may be possible by mid-June.\"

Smith Lyons is generally seen in the Toronto market as a second-tier corporate practice with a number of key players, such as David McFadden, Q.C., in corporate/ commercial and energy and Paul Harricks in corporate finance. It has an important insurance practice. And, in the merciless talent wars that characterize the Toronto market, it has recently taken a number of major hits, i.e. Paul Mantini who left for Bennett Jones and Frank Davis who left for Donahue Ernst & Young LLP. While a highly regarded and important practice, the addition of Smith Lyons is not seen by the Toronto market as propelling Gowlings into the big leagues of corporate work.

What the potential Smith Lyons merger does provide Gowlings with is mass (see chart on opposite page). Simply put, the numbers transform the legal landscape. At 129 lawyers, Smith Lyons is the 24th largest law firm in Canada. At the end of the day, Gowlings would weigh in at about 730 lawyers, probably eclipsing McCarthys as the largest law firm in Canada. In the all-important Toronto market Gowlings would again eclipse or at least be within spitting distance of McCarthys and Blakes as the largest firm in the city.

Not bad for a firm and a junior associate who started from a position in Toronto in 1980 where \"many of the Bay Street firms didn\'t even notice our arrival.\" And there is absolutely no question that bragging rights as Canada\'s largest law firm are a valuable commodity, domestically and particularly internationally. With the right marketing team, the possibilities are considerable.

Yet what do these numbers mean? Assuming the Smith Lyons merger proceeds, Gowlings may be larger than McCarthys, more than twice the size of Stikeman Elliott, Oslers, and Ogilvy Renault, and almost three times the size of Torys and Bennett Jones. Yet no one argues that these numbers will put Gowlings in the same league as these firms. Nevertheless, what are the implications?

Is there a relationship between size and success? For Gowlings, this is a high-stakes, high-risk gamble. BCE is the largest telecom in Canada. But, as Jean Monty ruefully noted, unless it was able to successfully \"package\" new digital services, BCE would eventually be relegated to the role of a low-margin provider of wholesale network capacity.

Business law, IP, and advocacy are what Jolliffe calls Gowlings\' \"core practice areas.\" Of the three, IP is the firm\'s standout department that distinguishes it from Canada\'s other large, full-service firms. Jolliffe himself is one of Canada\'s top-ranked IP litigators. Among the major full-service firms, IP is Gowlings\'s competitive advantage.

The market position enjoyed by IP boutique practices in Canada is remarkable. Smart & Biggar is the largest with offices in Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Vancouver. Bereskin & Parr is the largest in Toronto. Other notable Toronto practices include Deeth Williams Wall LLP, Dimock Stratton Clarizio LLP, and Sim, Hughes, Ashton & McKay. In Montreal, Léger Robic Richard is a major practice. In Vancouver, there is Oyen Wiggs Green & Mutala.

Ogilvy Renault is the only other major full-service firm whose IP department, led by the legendary Joan Clark, Q.C., in Montreal, comes close to the profile that IP has at Gowlings. However, Ogilvys IP practice does not have a national presence, whereas Gowlings has extended its IP presence to Calgary, Montreal and Vancouver, following its mergers in each of these cities.

All of this is not to say that the other major full-service firms do not have significant IP practices. They do. Lang Michener in Toronto boasts one of the country\'s top IP litigation departments, headed by Donald MacOdrum, who appeared as counsel in Lubrizol v. Imperial Oil and Beloit v. Valmet, two of the largest cases in Canadian patent litigation history. Blakes has one of the oldest and deepest IP departments among the top-tier business law firms, with Sheldon Burshtein and Brian Gray enjoying national reputations. McCarthys, Faskens, Oslers (particularly in Ottawa with Glen Bloom) and Borden Ladner (again particularly in Ottawa as a result of its merger with Scott & Aylen) have significant IP resources. But none of these national firms has the depth, range of service, or reputation that Gowlings enjoys.

Among the nationals, only the Gowlings brand is inextricably identified with IP. \"At most other big firms, IP tends to be an adjunct,\" says Jolliffe. \"At Gowlings, IP is a drawing card.\" James Kokonis, Q.C., a partner at Smart & Biggar, and one of Canada\'s most senior IP practitioners, provides a similarly blunt assessment of the market when he notes that his firm \"looks only at Gowlings and Ogilvy Renault as our competition among the big firms.\"

Gowlings\' unique IP strength among the majors is the key to its business law strategy, which is grounded in what has fashionably become known as convergence: the coming together of IP, IT and high-end transactional business law practices. The leveraging of IP into a strong IT practice has assumed the status of conventional wisdom in the knowledge-based New Economy. Transactional work aside, the commercial work involved generates huge legal fees. Witness, for example, the Bank of Nova Scotia\'s recent $900 million outsourcing of its internal technology to IBM, followed closely by CIBC\'s $227 million outsourcing of its technology and human resource operations to EDS Canada.

\"We blend IP and IT and cross-sell them,\" says Amy-Lynne Williams of Deeth Williams Wall, whose 16-lawyer firm was one of the first to embrace convergence when its founding partners left a major Toronto firm to found their IP/IT boutique in 1994. Similarly, Montreal\'s Léger Robic Richard has successfully integrated six commercial lawyers into its rapidly expanding IP/IT practice.

Further confirmation as to the role IP plays in the current strategic thinking of lawyers comes from Gregory Turnbull in Calgary who advises that the IP strength of Gowlings was key to his predecessor firm\'s decision (i.e. Code Hunter) to merge with the larger firm. \"The Gowlings nameplate opens a lot of high-tech and e-commerce doors around here,\" says Turnbull.

And soon after the merger, Gowlings recruited Macleod Dixon\'s John Ramsay, Q.C., one of the most prominent IT lawyers in Western Canada, to the firm\'s new Calgary office. \"I left Macleod Dixon because I was always an appendage with a very powerful energy firm,\" Ramsay says. \"I had expertise law firms would die for, but Macleods didn\'t understand what I was doing or the culture of my practice. There weren\'t a lot of people I could talk to and get backup from on the technical side. Now I have the depth of the patent people at Gowlings, which leads me to a lot of other work, like international licence work with cross-border tax issues that I wouldn\'t see at my old firm. The move is an opportunity for me to mine Gowlings\' patent clientele and convert it to the type of work I do.\"

Catapulting an IP/IT practice, even a strong one, into a top-tier national corporate practice is a daring gamble on which Gowlings, from all appearances, has mortgaged its future. \"Our overheads, especially our space and our wages, are top-tier,\" says Jolliffe. \"We are past the point of no return.\"

Some elements of the strategy seem unassailable. The stakes are huge. Every major law firm in Canada is parading its New Economy skill set, usually some version or combination of IT and/or e-commerce. This is because the traditional mainstays of the Old Economy, like financial institutions, are at the forefront of e-commerce implementation and expansion. Firms who wish to continue servicing the lucrative transactional market, for Old Economy clients entering the New Economy or for emerging New Economy clients, are dead in the water without an IP and/or IT capability. \"The IP professional takes a very prominent role at the boardroom table these days,\" says Jolliffe.

But the apparent corollary--that firms with IP and IT strength have, by virtue of that expertise alone, what it takes to crack the top-tier transactional corporate market--does not necessarily follow. The difference is in the quarterbacks and bench strength. The quarterbacks are the corporate stars, i.e. the lawyers at the top-tier firms with the reputation for negotiating, structuring and bringing home a deal. To analogize from the situation at BCE as described by Jean Monty, these are the lawyers who are able to successfully \"package\" new digital services. The bench strength has to do with a firm? reputation and depth in the related practice areas that are essential to top-tier transactions, such as tax, securities, corporate finance, corporate restructuring and increasingly, IP and IT.

The skills that the quarterbacks bring to the table, however, have little to do with IP and IT expertise, any more than they have to do with an encyclopedic knowledge of the Income Tax Act. Rather, the quarterbacks generally bring a deep knowledge of corporate structuring and finance with an ability to quickly grasp the importance and role of whatever tax, IP, or other such issues are involved. They must know enough about all the issues to ask the right questions and demand the right answers without necessarily providing those answers themselves.

The quarterback\'s skill, in the end, is one of judgment and experience. And in that sense, as in many others, the stronger are getting stronger. The top-tier business law firms nurture their deal makers, securing their future by building expertise in those areas of the law that the evolution of the economy--and the protection of their quarterbacks--require. Quarterbacks are a much more valuable commodity than linemen.

\"Pure IP lawyers don\'t have the pragmatic base that grounds reality in the corporate world,\" says Sally Daub. And she should know. Daub is a lawyer and registered patent agent with an engineering degree who first practised at Smart & Biggar, then as a patent counsel at Nortel, and is now President and CEO of ViXS Systems Inc., a company that provides video technology-related network solutions. \"Typically, on a major corporate transaction, I would look for a firm that has individual lawyers with strong corporate, commercial and tax reputations,\" she says. \"They are the ones who run the big deals.\" And a senior corporate with one of Canada\'s largest companies, who spoke off the record, was equally blunt: \"We put our IP business with IP firms, and our large corporate commercial deals with firms that have the reputation and capacity to do that work.\"

Jolliffe recognizes that, without quarterbacks, a top-tier business law practice will be hard to come by. \"The clients who have grown after starting with us as IP or IT clients, stay with us for their transactional business. But the emerging and mid-size businesses that spring from an IP/IT practice do not engage in the large restructuring and acquisition work that we need to round out our practice. And the large clients who come to us for specialized IP work frequently take their transactional business elsewhere.\" This hard reality leads Jolliffe to only one logical conclusion: \"Gowlings must develop a tier-one business law practice that is independent of its reputation in the IP field.\"

Gowlings\' strategy unfolds as follows: build a national platform across the country by merging with local firms that can provide the basis for a business practice; give the merged firms a competitive advantage over the other nationals by providing them with a local and nationwide IP and IT base (including imports from Gowlings\' strongholds in Ottawa and Toronto) to attract emerging clients and specialty work from traditional large clients; grow with the emerging clients; and use the critical mass and reputation generated by the size of the national platform and its competitive IP/IT advantage to attract top-tier work.

The first question that arises is will this strategy lead to a \"tier-one business law practice\" without the additional recruitment of senior corporate quarterbacks? The second question is what makes Gowlings think it can maintain its competitive IP advantage (and all that this entails) vis-à-vis the majors? Other people recognize a good thing when they see it. McCarthys has built a huge national IT practice. In Toronto, Torys, Oslers, and others have similarly built significant IT practices (see \"The Rise of the E-commerce Lawyer,\" Lexpert, September 2000). Simply put, how secure is Gowlings\' IP competitive advantage? It? an important question. The first rule in establishing any beachhead is secure your flanks.

Gowlings\' IP base has been and remains critical to its strategy in three ways: first, as a means of attracting law firms to the fold (which it has done); second, as a critical component of the IP/IT practice convergence directed at the emerging business market; and third, as an initial draw to top-tier business clients interested in the firm\'s IP expertise (bait and switch if you will).

What this means is that the firm must, at the very least, hold its own in the now very competitive IP market. And if the American experience is any indication--and with increasing frequency it has been in various legal market sectors--full-service business law firms should have already become more active in the IP market, most likely by way of merger or lateral transfer from the boutiques that play such a strong role in IP law in Canada.

Starting in the mid-1980s, in response to client demand, a number of US full-service business law firms, including 400-lawyer Boston-based Hale and Dorr LLP, began recruiting IP professionals. The trend accelerated in the early and mid-1990s when, according to Hale and Dorr senior partner Gary Walpert, \"IP became pistol-hot as the dot.coms emerged, patents became more important, and patent litigation proliferated. The landscape changed and general firms began merging with small and large IP firms. They did it to provide one-stop shopping for clients who needed work done at the US Patent Office, and to get a piece of what has become a hugely profitable patent litigation practice.\" The strategy worked for Hale and Dorr, which now has over 100 professionals doing IP- and IT-related work.

The larger boutiques, such as New York\'s 175-lawyer Fish & Neave, retained their independence by expanding to provide a full range of IP services, including licensing and due diligence work. \"The bigger, older IP firms in this country are still around,\" says Fish & Neave senior partner Herbert Schwartz, one of the top patent litigators in the US. \"It\'s the smaller firms that have been swallowed up.\"

In Canada, however, the major full-service business law firms have met with mixed success in building their IP practices. It is not for lack of trying. We\'re talking major unrequited affection here. Virtually every IP boutique of significance interviewed for this article confirms multiple approaches from various large firms. Yet everyone, to date, has said no. And unless a major brings a significant IP boutique on board, it will be hard to mount any meaningful assault on Gowlings\' position in this market.

Part of the reason for the interest on the part of majors is that much of what is done in an IP/IT practice is also done in IP boutiques. \"The basic licensing of rights and the basic acquisition of IP has always been viewed as part of the IP field, so we could call ourselves IT lawyers,\" says Brian Isaac at Smart & Biggar. Cynthia Rowden at Bereskin & Parr agrees: \"IP boutiques encompass the framework for protecting the technology and advising IP owners about the commercialization and exploitation of their property.\"

\"The boutiques have remained on their own,\" says James Kokonis at Smart & Biggar, \"partly because we\'re successful on our own, partly because we don\'t want the problems that you have with multiple departments in large firms, and partly because, in our case, joining a large firm might ruin the important relationships we have with about 30 American firms and 400 or 500 firms worldwide that refer business to us.\"

The inherently international nature of IP practice and its multidisciplinary nature are factors that favour Gowlings maintaining its competitive IP edge vis-à-vis the other full-service firms. \"IP lawyers must be part of an international network, which requires a lot of travelling and investment in publicity and promotion,\" says Hugues Richard of Léger Robic Richard in Montreal. \"A managing partner who is a corporate or insurance law specialist won\'t understand why you have to go to three international conventions a year.\" Roger Hughes, Q.C., at Sim, Hughes, Ashton & McKay in Toronto develops the argument further: \"Most of the big firms still have a structural or corporate ethic that doesn\'t give non-lawyers their dues, so patent agents or people with Ph.D.s who work there tend to be positioned somewhere between the articling students and the law clerks.\" By way of contrast, Gowlings has registered as a multidisciplinary partnership and inducted its non-lawyer patent agents as full partners.

A second flank that Gowlings must protect is IP litigation, which is big business both in Canada and the United States. Here again, the question arises as to whether Gowlings will be able to maintain its competitive IP edge vis-à-vis the other full-service firms.

\"Many large firms have courted us because they see that IP litigation is very lucrative,\" says Ronald Dimock at IP boutique Dimock Stratton Clarizio. Just how lucrative is evidenced by the decision of New York-based securities class-action heavyweight Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach LLP to enter the field by representing small companies, which allege that larger enterprises have infringed their patents. This is big money. Milberg Weiss has a reputation for not wasting its time on small change.

Although damages in Canadian IP litigation pale alongside those awarded in the US, the amounts at stake can still be breathtaking. Paul Morrison at McCarthys acted for Unilever on the damages hearing before Mr. Justice George Adams arising out of the Unilever/Proctor & Gamble patent infringement \"Bounce\" dryer-added softening sheet litigation. Unilever was the successful litigant. Lorne Morphy, Q.C., and Sheila Block at Torys acted for Proctor & Gamble on the hearing. It is said that the matter settled for well over $100 million.

Morrison\'s involvement, as well as that of Morphy and Block, exemplifies an American trend where commercial litigators have made inroads in a field traditionally reserved for IP specialist litigators. \"Clients want a commercial litigator leading the team in complex litigation,\" says Morrison. \"They feel we can master technical evidence and have the experience to marshal it, lead it, and strategize what will be persuasive.\"

Nevertheless, even a cursory survey of recent law reports reveals only a small number of commercial litigators on reported IP litigation cases, and the patent litigation specialists interviewed for this article contest any movement from IP specialists to commercial litigators. \"We\'re going gangbusters,\" says Roger Hughes at Sim, Hughes, who, like many of his boutique colleagues, simply can\'t find enough lawyers to meet his firm\'s workload. \"Patent litigation in our firm is booming, and copyright and trademark litigation is also very active,\" confirms Robert MacFarlane of Bereskin & Parr.

Close comparison of the Canadian and US patent litigation systems provides several explanations as to why the American move to corporate litigators will not likely be repeated in Canada. To begin with, patent cases in Canada are generally litigated in the Federal Court, while American cases are tried in the general commercial courts. In US courts, damages are awarded by juries, making the advocacy skills of general litigators as critical, if not more critical, than their technical knowledge. In Canada, juries have no involvement in IP trials.

The success rate for plaintiffs also differs. According to Ronald Dimock, who has carried out a statistical analysis, 60 per cent of infringement cases fail in Canada, while a growing majority succeed in the patent-holder friendly US courts. The treble damages remedy is available in the United States, where the market is also much larger and the cases much bigger, attracting more commercial litigators. And finally, explains Cynthia Rowden, the major business law firms tend to represent Canadian subsidiaries of foreign corporations: \"Because patent litigation tends to be international in scope, it is the parents who manage the litigation, and they are accustomed to dealing with the specialty firms.\"

\"The firms with patent litigation expertise will always have an edge and their overall IP expertise is highly valued,\" says Sally Daub at ViXS. \"And the more technical the intellectual property at issue, the more important is that expertise.\" Daub is skeptical that the involvement of McCarthys and Torys in the \"Bounce\" litigation is a portent of future developments. In her view that particular matter, given the nature of the product, did not place high technical demands on counsel.

While the international nature of IP practice works to protect Gowlings\' flanks in terms of its competitive IP edge vis-à-vis the other full-service firms, it also works against Gowlings\' ambitions to become a top corporate practice. The fact is that the organizational structure of many large companies does not facilitate Gowlings\' convergence strategy, i.e. levering off its IP expertise into corporate matters. As noted by Cynthia Rowden at Bereskin & Parr, in the case of international clients, it is the parents of the Canadian subsidiaries that tend to direct the IP work. And, generally speaking, the parent\'s patent counsel does not report directly to the general counsel\'s office. Patent work is usually assigned by the parent\'s patent counsel or by an IP firm from the home country of the parent.

At IBM, for example, Leonora Hoicka is a Toronto-based staff counsel with global responsibility for managing the company\'s software and applications patent portfolio. The four other lawyers in her group are US-based, and all five lawyers report to an associate general counsel. The associate general counsel reports to a vice-president of international property law and licensing, who in turn reports to the general counsel.

Despite this organizational barrier, Hoicka believes that IP is a marketing contact \"that\'s exploitable for law firms.\" The greatest opportunities for expanding legal work through IP connections, Hoicka adds, may lie with IP litigation counsel \"because their performance in litigation is probably of greater general interest [than prosecution work] within the company and presents a better opportunity for a firm to become known. It hasn\'t happened yet, but it\'s reasonable. It\'s just a matter of finding the right contact to get a law firm the pass through.\"

However, sources familiar with IBM\'s allocation of legal work in Canada maintain that there is a stiff resistance both among patent counsel and general counsel in retaining the same firm for IP and corporate/commercial work. That doesn\'t surprise Gary Walpert at Hale and Dorr in Boston. \"There is a tendency for IP clients to look at their IP firms solely as IP firms. One of my major difficulties is getting clients to call me for transactional work.\" And this is a senior partner from one of the US convergence success stories speaking.

Still, Gowlings has demonstrated that using IP work to leverage corporate/commercial work from large international clients is, as Hoicka says, \"reasonable\". Jolliffe cites pharmaceutical giant Hoffmann-LaRoche and Uniroyal (now Michelin) as IP clients who have grown into general commercial clients. Impressive examples of the IP/IT convergence model working would also include PixStream/Cisco and the new Mitel. Tom Hunter of the firm\'s Waterloo office, who has represented PixStream Incorporated since its inception in 1996, led the Gowlings team when US tech-giant Cisco Systems, Inc. bought PixStream for $554 million last year. More significantly, Gowlings now represents Cisco in Canada. Brian McIntomny and Wayne Warren of the Ottawa office represented Dr. Terence H. Matthews earlier this year in the $350,000,000 acquisition of a 90 per cent interest in the worldwide telecommunications system business previously operated by Mitel Corporation. Again, Gowlings now represents the new Mitel generally.

Bay Street pundits call the PixStream and Mitel examples isolated instances, arguing that it is impossible to generate the deal flow necessary to sustain a top corporate practice by leveraging off IP/IT alone. The price of entry to top-tier corporate work, they argue, is top-tier corporate practitioners, i.e. quarterbacks. Mid-market work leveraged off IP/IT they will concede. But not a top-tier corporate practice. And this is the other question arising from the Gowlings strategy. Can a \"tier-one business law practice\" be built without the additional recruitment of senior corporate quarterbacks.

The fact is that Scott Jolliffe is attempting to do what no firm anywhere in the world has done: leverage a specialty IP/IT business beyond the mid-market into a top-tier transactional firm. There are analogous situations, such as the convergence of technology and finance that was behind the aborted 1999 trans-Atlantic merger between San Francisco-based Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe and the UK\'s Bird & Bird. \"It was certainly a mouthwatering process,\" wrote Ben McLannahan in the April 2000 issue of Legal Business. \"Bird & Bird, top-ranked in The Legal 500 for its IP, IT, digital media and telecoms practices, allied to Orrick, whose West Coast banking and corporate practices are a fixture in the top tiers of The Asia Pacific Legal 500.\"

For the purposes of analysis, it is the last point made by McLannahan that is relevant. It sets out the fundamental and critical difference between the proposed Orrick/Bird & Bird merger and Gowlings. Orrick had an established top-tier banking and corporate practice. Gowlings does not. In Canada, Ogilvy Renault has done an excellent job of leveraging its IP expertise into high-end corporate work. But Ogilvy has historically been one of the top-ranked corporate firms in Quebec. And, when the firm entered the Toronto market, one of its first moves was to establish corporate credibility by recruiting top corporate talent.

There are other analogies, but they also fall short of the Gowling situation. New York-based Brown Raysman Millstein Felder & Steiner LLP, recently associated with Toronto\'s Mann & Gahtan LLP, has developed one of the broadest IP/IT practices in the US, servicing emerging clients from start to finish and doing specialty work for huge companies. \"But we\'re not expending our efforts on being picked for the $5 billion pure acquisition, because someone else has had the inside track there for a long time,\" says name partner Peter Brown. Similarly, London-based Bristows in the UK, in the words of Managing Partner Ian Judge, is \"an IP-led full-service firm for corporations with interests in IP or technology.\" Bristows is undoubtedly one of the top IP firms in the UK, but its client base for corporate matters is mid-market.

No less an authority than senior Ogilvy Renault IP practitioner Patrick Kierans, where IP and business law are two of the firm\'s \"four pillars,\" believes that Gowlings\' strategy is a \"natural extension of its IP strength and strong commercial presence.\" Yet the question is where that IP strength will take you. Conventional wisdom has it that it won\'t take you into the top tier of corporate work. Jolliffe understands this.

In a matter of months Scott Jolliffe may be the National Managing Partner of the largest firm in Canada. He is a quiet, gracious man who speaks with disarming honesty. \"If it is to be a short transition--five years is too long for us,\" Jolliffe says, \"then we need the tier-one player.\" Pundits would say players. That\'s the decision that has to be made. Go long and build from the national platform on the corporate side. Or go short and use the national platform to recruit quarterbacks from the top tier. To go short will be very expensive, but it may pre-empt the defections that generally follow law firm mergers. To go long runs the risk of not meeting expectations that may have been created by the mergers. Jean Monty at BCE has already made his decision. He has short-fused investors that have to be dealt with. Monty\'s going short.

Julius Melnitzer is a Toronto legal affairs writer.