Updated June 20, 2024

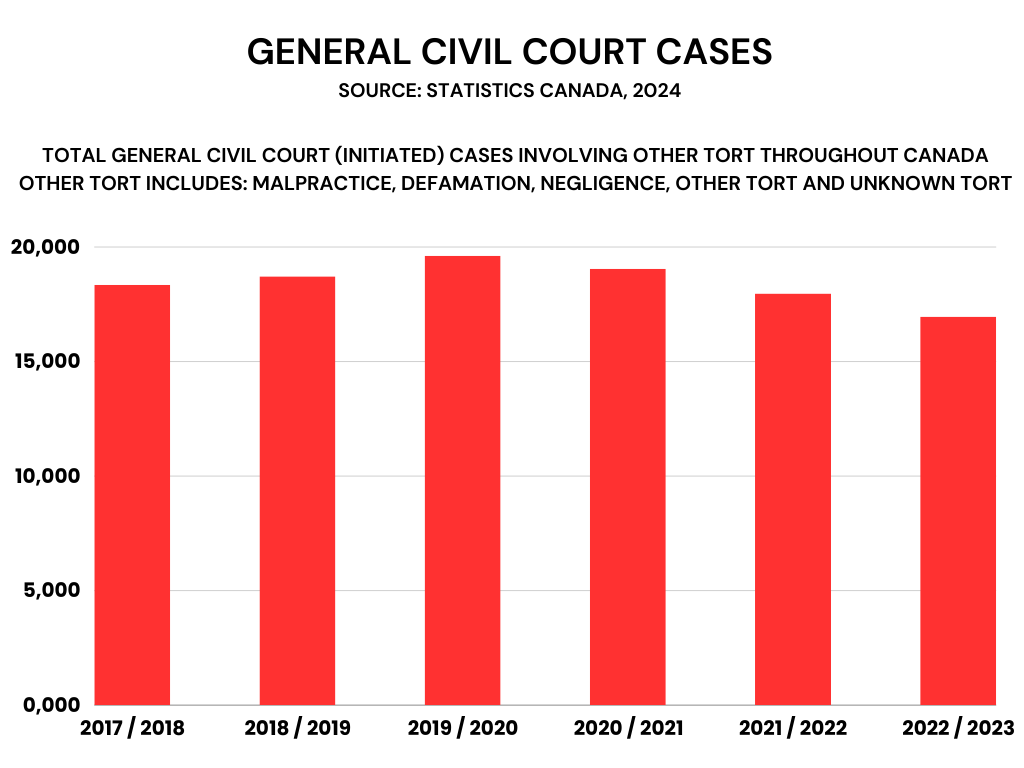

Although lawsuits for malpractice are lower than in previous years — but with potentially higher values — more suits could be filed in the future. There has also been a reported increase in complaints to regulatory colleges and hospitals. All of these are part of the evolution of medical malpractice lawsuits in Canada.

What are medical malpractice lawsuits?

Medical malpractice lawsuits broadly cover the claims filed against medical practitioners by their patients or the patients’ families. It may be due to one of the following:

- medical negligence

- breach of duty

- breach of contract

When injuries result from these causes of action, a claim for damages arises against the erring medical practitioner. The amount of compensation would vary in each case, following the standards set by the law.

When it comes to the defendants of these lawsuits, the medical professionals may include the following, among others:

- physicians

- surgeons

- nurses

- pharmacists

Because of the principle of vicarious liability in tort law, hospitals may also be held liable for the actions of their employees.

For a brief explainer on what medical malpractice lawsuits in Canada are, watch this video:

If you’re looking for lawyers to help you with your medical malpractice lawsuit, check out our directory of the Lexpert-ranked best personal injury lawyers in Canada.

How did medical malpractice lawsuits evolve over the years?

As the medical field has grown over the years, cases involving medical professionals have also increased. There are also factors to consider, such as the presence of a system to receive complaints, plus the expanding legal system to address malpractice and medical negligence.

Technological changes improving malpractice lawsuits

One of the most significant developments over the years in medical malpractice lawsuits is technology and the internet. What was once costly and difficult to achieve in the pre-internet era can now be easily done.

“With the ability of virtual platforms, I can serve clients much more effectively and efficiently outside of Ontario,” said Paul Harte, the principal of Harte Law PC. Although the firm’s practice is predominantly in Ontario, it also extends nationally, thanks to technology.

“Victims of medical malpractice find it hard to get justice at the best of times, and in smaller communities, it’s hard to get local representation,” said Harte, who practises almost exclusively on the plaintiff side. “Given the changes in the courts’ acceptance of virtual hearings, it’s really opened up other areas of the country to our firm.”

The use of technology has made a huge difference, particularly because medical experts are often required to testify in medical malpractice cases. It can be challenging to get these busy professionals into court. But now, experts can appear virtually.

More remote witnesses and visuals in trials

During trials, the use of modern technology has become useful when proving medical malpractice claims. This applies to presenting remote expert witnesses and other visuals during trial.

“I had a trial involving an expert in Boston and an expert in the UK,” Harte said. “Both of those experts testified virtually, saving a huge amount of time in terms of travel costs but also allowing greater flexibility to accommodate their schedules.”

In virtual hearings, litigators can use visuals in remote presentations instead of simply talking to a decision-maker in a room. Harte recently made a PowerPoint presentation before an appellate court since sharing a screen is easily done in virtual proceedings.

Trends reflecting the current medical scene

More laws have been passed over the years addressing medical malpractice.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some laws were also passed to address the medical climate at that time. An example of these laws is Supporting Ontario’s Recovery Act.

In response to the pandemic, health-care professionals were required to act reasonably and outside of their defined scope of practice and take on additional responsibilities. This may explain the higher number of malpractice claims during the pandemic.

Robust common law on medical malpractice lawsuits

Part of the Canadian legal system is common law principles. These are the guiding precedents for new and future cases, such as for medical malpractice lawsuits. While most of these cases are rehashed versions of older principles on prosecuting and claims for medical malpractice, there are other new pronouncements. Here are some of these important cases that are part of the evolution of medical malpractice in Canada:

Sylvester v. Crits et al., [1956] S.C.R. 991

The classic case where the Supreme Court, as it affirmed the Court of Appeal of Ontario, established the standard of care that is expected of physicians. The case said that it is “that degree of care and skill which could reasonably be expected of a normal, prudent practitioner of the same experience and standing.”

The Court added that if a medical practitioner “holds himself out as a specialist, a higher degree of skill is required of him than of one who does not profess to be so qualified by special training and ability.”

Clements v. Clements, 2012 SCC 32, [2012] 2 S.C.R. 181

An important case law reiterating causation as an element of personal injury cases, which also applies to medical malpractice lawsuits. Here, the Supreme Court held that a plaintiff in a personal injury case must establish that the defendant’s negligence (breach of the standard of care) is the cause of their injury. This is aside from offering proof that the defendant was negligent.

With this, the Court established the “but for” test, which states that the “plaintiff must show on a balance of probabilities that 'but for' the defendant’s negligent act, the injury would not have occurred.”

Taylor v. David, 2022 ONCA 200

Limitation periods have always been a good defense against medical malpractice lawsuits. This is why provincial limitation statutes are always a subject of affirmation and interpretation by succeeding case law.

In this case, the plaintiff’s claim was dismissed because it was filed after the 15-year prescriptive period provided by the Ontario Limitations Act. This case, along with others based on provincial Limitations Acts, guides plaintiffs and their lawyers to file their claims on time.

Onset of class actions on medical malpractice

While the subject matter of class actions may be past significant events of collective value, its use to institute claims has been more apparent over the years. These types of claims, whether against the government and larger organizations, have gained traction because of the idea of “the greater the number, the higher the chances of winning.”

It also helped that existing class action statutes have been recently amended to reflect some of the developments in how class action should work.

In Ontario, the province’s Class Proceedings Act, 1992 was recently amended, which came into force on October 1, 2020. The counterpart law of British Columbia, also named Class Proceedings Act, was also recently amended and came into effect in 2018 and in 2022.

Currently, more and more class actions have been filed, certified by the court, or dismissed in recent years. This only shows that class actions are an important tool when a case involves several plaintiffs.

Some examples of the more recent medical malpractice class lawsuits are:

- British Columbia: Massie v. Provincial Health Services Authority, 2023 BCSC 1275

- Ontario: Barbiero v. Pollack, 2024 ONSC 1548

- New Brunswick: Jayde Scott, on behalf of herself and other class members v. Regional Health Authority B, dba Horizon Health and Nicole Ruest, 2023 NBKB 209

Improving professional regulation to prevent lawsuits

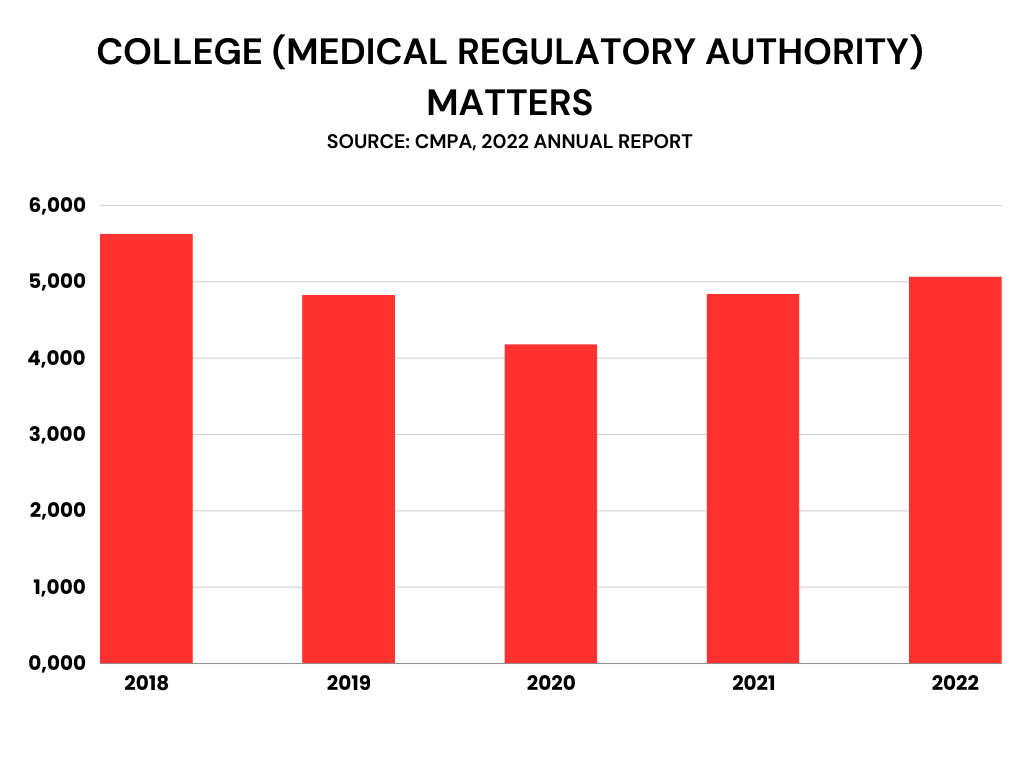

Lawsuits have flattened in recent years according to Valerie Prather, co-head of health practice for Bennett Jones LLP. However, there’s been a significant increase in complaints to medical colleges and hospitals, and the complaints aren’t just about medical care.

“We see complaints about communication issues, that [patients] weren’t treated fairly or nicely,” she said. “With that increase in complaints, the colleges and hospitals have a backlog to deal with.” Resolving complaints in a timely fashion is resource intensive. Hospitals also control doctors’ privileges, which they can withdraw.

Professional regulatory complaints may arise from the trend toward providing virtual care, referring to experience during the pandemic. “Whenever you have to transition into using a new type of system, there are, unfortunately, opportunities for things to fall through the cracks or to be frustrating for people, and that leads to complaints,” Prather said.

Nevertheless, pandemic or none, cases of regulatory and college complaints have only been managed, but never eliminated. As these cases are being filed, they’re also an indicator of the patients’ trust in the system, in the hopes that it can address the injuries they’ve suffered.

Room for improvement through experience

The flush of new common law to become a basis, and with new statutes being passed, for legal matters within the medical field are continually improved. As such, there’s always this room for improvement using these new legal precedents.

Harte has also noticed a recent trend toward increased transparency in professional regulation. When a doctor is found to have made a major error in judgment or failed to meet a standard of care, the provincial regulatory websites publish those major misses.

“There’s always room for more transparency, but the regulations over time have slowly shifted, and attitudes toward what the public is entitled to know about their doctor, the person they’re entrusting their health and safety to — that has created some improvement,” Harte said.

Medical malpractice lawsuits in Canada: here to stay

In an ideal world, there would be no medical malpractice lawsuits. No families would be injured because of malpractice or negligence, and no medical professionals would be brought to court. But as modern society moves to achieve such a world, the country’s justice system is here to protect the rights of both parties, and to compensate what has been lost on the part of the plaintiff. As medical malpractice lawsuits continue to evolve, one thing’s for certain — it’s here to stay, for better or for worse.

Interested in knowing more about medical malpractice lawsuits? Reach out to the best medical negligence lawyers in Canada as ranked by Lexpert.